Platelets

Short Notes

- Platelets can be collected as a component of whole blood donation or through apheresis.

- A standard adult unit of platelets averages about 300ml and will typically raise the platelet level by 20-40 x10^9/l.

- Platelets are stored at 20-24oC under constant agitation for up to 5 days.

- Though abnormalities of platelet action can be divided into either quantitative (related to the total number) or qualitative (related to the actual function of the platelets), it is only really the number of platelets that determine when to transfuse.

- Transfusion thresholds are primarily based on expert opinion and limited clinical evidence from patients with haematological conditions.

- If there is no active bleeding or planned trauma (i.e. surgery) then a threshold for transfusion of 10 x 10^9/l is used.

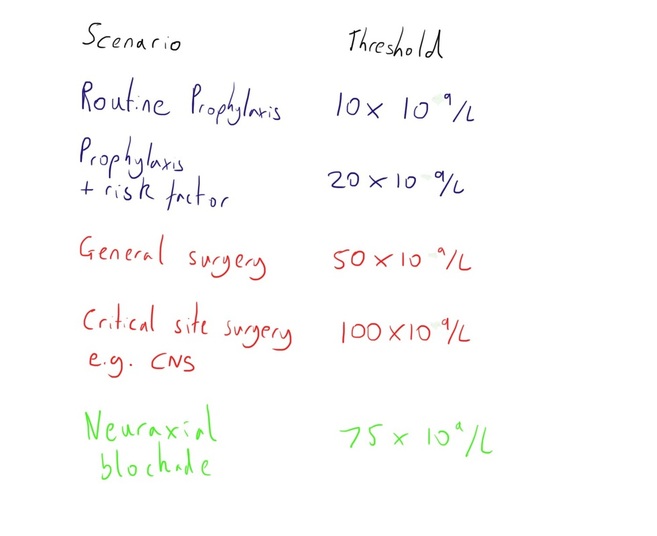

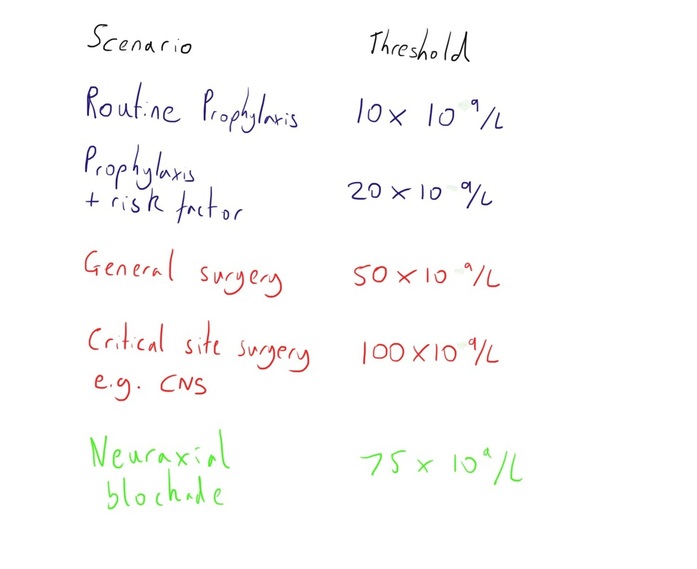

- If planned trauma is upcoming, the nature of the intervention is a determining the threshold, which are highlighted in the diagram below.

- Complications from platelet transfusion are similar to those with red cell transfusion.

Long Notes

Collection

Platelets can be collected as a component of whole blood donation or through apheresis, where the platelets come from a single patient.

With centrifugation of whole blood, it is the buffy coat contains the platelets, with pooling of this layer from 4 different donations to create one adult unit.

One standard adult unit averages about 300ml.

The paediatric dose is 5-10ml/kg.

With centrifugation of whole blood, it is the buffy coat contains the platelets, with pooling of this layer from 4 different donations to create one adult unit.

One standard adult unit averages about 300ml.

The paediatric dose is 5-10ml/kg.

Storage

Platelets are stored at 20-24oC under constant agitation.

They are stored with the initial preservative of citrate phosphate and dextrose (CPD) that is added during initial collection.

They can be stored for up to 5 days.

Given the elevated temperature they are at higher risk of bacterial contamination, hence the shorter shelf life. However, if pathogen inactivation processes are undertaken this may be extended to 7 days.

They are stored with the initial preservative of citrate phosphate and dextrose (CPD) that is added during initial collection.

They can be stored for up to 5 days.

Given the elevated temperature they are at higher risk of bacterial contamination, hence the shorter shelf life. However, if pathogen inactivation processes are undertaken this may be extended to 7 days.

Clinical Use

Platelets are a central component of the body’s haemostatic mechanisms, providing a base and many important mediators for the coagulation process to occur.

The process is covered in more detail here: http://www.medicalphysiology.co.uk/haemostasis.html and http://www.medicalphysiology.co.uk/platelets.html

The process is covered in more detail here: http://www.medicalphysiology.co.uk/haemostasis.html and http://www.medicalphysiology.co.uk/platelets.html

Abnormalities of platelets can be roughly divided into two domains:

The normal range for platelets is 150-450 x 10^9/l.

Severe thrombocytopenia is typically defined as levels below 50 x 10^9/l

One unit of platelets will typically raise the platelet level by 20-40 x 10^9/l.

- Quantitive – Inadequate number of platelets for function

- Qualitative – The platelets present have impaired function

The normal range for platelets is 150-450 x 10^9/l.

Severe thrombocytopenia is typically defined as levels below 50 x 10^9/l

One unit of platelets will typically raise the platelet level by 20-40 x 10^9/l.

Transfusion Thresholds

Transfusion of platelets will generally be for either one of two indications:

In active bleeding platelets will often be used as part of major haemorrhage packs/protocols.

There may also be a role for laboratory test guidance for transfusion, particularly those such as thromboelastography, though the rapid changing clinical picture in bleeding patients may limit this (and hence the development of major haemorrhage packs).

In active bleeding, platelet levels should be kept above 50 x 10^9/l or 100 x 10^9/l if there is concomitant coagulopathy or the risk of CNS bleeding.

- Active bleeding

- Prophylaxis against bleeding

In active bleeding platelets will often be used as part of major haemorrhage packs/protocols.

There may also be a role for laboratory test guidance for transfusion, particularly those such as thromboelastography, though the rapid changing clinical picture in bleeding patients may limit this (and hence the development of major haemorrhage packs).

In active bleeding, platelet levels should be kept above 50 x 10^9/l or 100 x 10^9/l if there is concomitant coagulopathy or the risk of CNS bleeding.

The thresholds for prophylactic transfusion are primarily based on expert opinion, with little strong clinical evidence. Much of the evidence that exists comes from assessment of haematology patients with thrombocytopenia.

The thresholds are based around the consequences of bleeding if it occurred i.e. higher for sensitive sites, and will clearly vary if there is an expected need for platelet utilisation e.g. upcoming surgery.

The risk of spontaneous bleeding appears to increase below the threshold of 10x10^9/l, and hence this threshold is used as a threshold for transfusion even if there is no active bleeding or planned surgery.

The thresholds are based around the consequences of bleeding if it occurred i.e. higher for sensitive sites, and will clearly vary if there is an expected need for platelet utilisation e.g. upcoming surgery.

The risk of spontaneous bleeding appears to increase below the threshold of 10x10^9/l, and hence this threshold is used as a threshold for transfusion even if there is no active bleeding or planned surgery.

The clinical context should also be taken into account when determining the decision for transfusion.

Ongoing inflammation and infection increase the bleeding risk and therefore raise the threshold.

Mucosal bleeding and epistaxis are warning signs of bleeding risk, whereas petechiae generally aren’t.

Ongoing inflammation and infection increase the bleeding risk and therefore raise the threshold.

Mucosal bleeding and epistaxis are warning signs of bleeding risk, whereas petechiae generally aren’t.

There are a number of causes of low platelets (and impaired function), and though these thresholds are generally considered as applying regardless of the aetiology. Indeed, this appears to relate the paucity of evidence on such thresholds.

However, there are some clinical conditions of thrombocytopenia where platelet transfusion should be avoided due to concerns about thrombogenesis:

However, there are some clinical conditions of thrombocytopenia where platelet transfusion should be avoided due to concerns about thrombogenesis:

- Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura

- Heparin induce thrombocytopenia

- Idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura

There is little guidance available on the role of platelet transfusion in patients with bleeding on antiplatelet agents, with some studies even suggesting harm from transfusion.

References

1. Shah A et al. Evidence and triggers for the transfusion of blood and blood products. Anaesthesia. 2015. 70 (Suppl. 1): 10-19

2. Yuan S et al. Clinical and laboratory aspects of platelet transfusion therapy. UpToDate. Sept 2016. (Accessed 22nd Sept 2016, available at http://www.uptodate.com/contents/clinical-and-laboratory-aspects-of-platelet-transfusion-therapy)

2. Yuan S et al. Clinical and laboratory aspects of platelet transfusion therapy. UpToDate. Sept 2016. (Accessed 22nd Sept 2016, available at http://www.uptodate.com/contents/clinical-and-laboratory-aspects-of-platelet-transfusion-therapy)