Caudal Anaesthesia

Last edited 23rd Nov 2017 - Tom Heaton

Anatomy

In childhood the 5 sacral vertebrae fuse to form the large triangular sacral bone.

The posterior vertebral arches of the 5th sacral vertebra (and sometimes 4th and 3rd) fail to fuse, leaving the sacral hiatus.

This is covered by the sacrococcygeal ligament (a continuation of the ligamentum flavum), and acts as a possible point of entry to the sacral epidural space.

The sacral canal is a continuation of the lumbar canal, with intervertebral foramina providing exit points for the sacral nerves.

In adults and older children, the spinal cord ends at around the L1 level (L3 in infants and neonates), with the subarachnoid space continuing to the S1-S2 level (S3-S4 in infants and neonates).

Beyond this inferior part the nerves will have passed through the arachnoid and dura layers and enter the epidural space.

There is an increase in the connective tissue of this epidural space as children grow older, thus making the spread of anaesthetic less reliable (and not very reliable at all in adults)

The posterior vertebral arches of the 5th sacral vertebra (and sometimes 4th and 3rd) fail to fuse, leaving the sacral hiatus.

This is covered by the sacrococcygeal ligament (a continuation of the ligamentum flavum), and acts as a possible point of entry to the sacral epidural space.

The sacral canal is a continuation of the lumbar canal, with intervertebral foramina providing exit points for the sacral nerves.

In adults and older children, the spinal cord ends at around the L1 level (L3 in infants and neonates), with the subarachnoid space continuing to the S1-S2 level (S3-S4 in infants and neonates).

Beyond this inferior part the nerves will have passed through the arachnoid and dura layers and enter the epidural space.

There is an increase in the connective tissue of this epidural space as children grow older, thus making the spread of anaesthetic less reliable (and not very reliable at all in adults)

Indications

These are essentially the same as for lumbar epidural anaesthesia.

The unpredictability of cephalad spread of the anaesthetic agent means that it is more suitable when a more sacral (rather than lumbar) level of block is needed.

The analgesic goals can be related to both acute and chronic pain.

The anatomical changes that occur with aging have some negative impact on the reliability of this approach and so it is more commonly employed in paediatric anaesthesia.

However, before the age of 6 a block up to T10 level can be reliably acheived via this approach.

The indications can be subdivided into:

Both single shot and continuous infusion techniques are possible.

The unpredictability of cephalad spread of the anaesthetic agent means that it is more suitable when a more sacral (rather than lumbar) level of block is needed.

The analgesic goals can be related to both acute and chronic pain.

The anatomical changes that occur with aging have some negative impact on the reliability of this approach and so it is more commonly employed in paediatric anaesthesia.

However, before the age of 6 a block up to T10 level can be reliably acheived via this approach.

The indications can be subdivided into:

- Acute pain

- Postoperative analgesia - particularly in children and in ‘lower’ surgery (perineum, inguinal, urological, lower limb)

- Labour pain (historical)

- Chronic pain

- Lumbar radiculopathy

- Diabetic neuropathy

- Pelvic pain syndrome

Both single shot and continuous infusion techniques are possible.

Technique

Can be broken down into ‘the 4 P’s’:

- Preparation

- Positioning

- Projection

- Puncture

Preparation

This is essentially the same as for epidural analgesia.

A careful history (with any relevant investigations) is essential to identify the indication and any contraindications to the technique.

Informed consent should be sought with the patient (or parent) with a clear explanation of how it will be performed.

Full AAGBI monitoring is essential.

Heavy sedation or general anaesthesia may be employed prior to performing the technique in children (but not recommended in adults).

All equipment should be prepared beforehand.

The decision for single-shot or infusion will impact on this, including the choice of needle.

In children, a 20 or 22g cannula is a good choice, allowing removal of the needle after sacrococcygeal ligament puncture.

Careful aseptic technique is essential.

A careful history (with any relevant investigations) is essential to identify the indication and any contraindications to the technique.

Informed consent should be sought with the patient (or parent) with a clear explanation of how it will be performed.

Full AAGBI monitoring is essential.

Heavy sedation or general anaesthesia may be employed prior to performing the technique in children (but not recommended in adults).

All equipment should be prepared beforehand.

The decision for single-shot or infusion will impact on this, including the choice of needle.

In children, a 20 or 22g cannula is a good choice, allowing removal of the needle after sacrococcygeal ligament puncture.

Careful aseptic technique is essential.

Positioning

The goal of positioning is to optimise the ease of identifying the relevant landmarks (particularly important in adults) and making to performance of the block easier.

Several positions are possible:

The lateral decubitus position is often used in children, as it allows easier management of general anaesthesia/deep sedation.

The prone position is often employed in adults.

Here the table should be flexed, and a pillow placed under the hips/pelvis to allow some flexion at the hip joint.

Internally rotating the legs and having them feet placed slightly apart (an angle of 20 degrees) also helps with landmark identification by relaxing the gluteal muscles.

Several positions are possible:

- Lateral decubitus

- Prone

- Knee chest

The lateral decubitus position is often used in children, as it allows easier management of general anaesthesia/deep sedation.

The prone position is often employed in adults.

Here the table should be flexed, and a pillow placed under the hips/pelvis to allow some flexion at the hip joint.

Internally rotating the legs and having them feet placed slightly apart (an angle of 20 degrees) also helps with landmark identification by relaxing the gluteal muscles.

Projection/Puncture

Consideration of the landmarks is important to perform the technique.

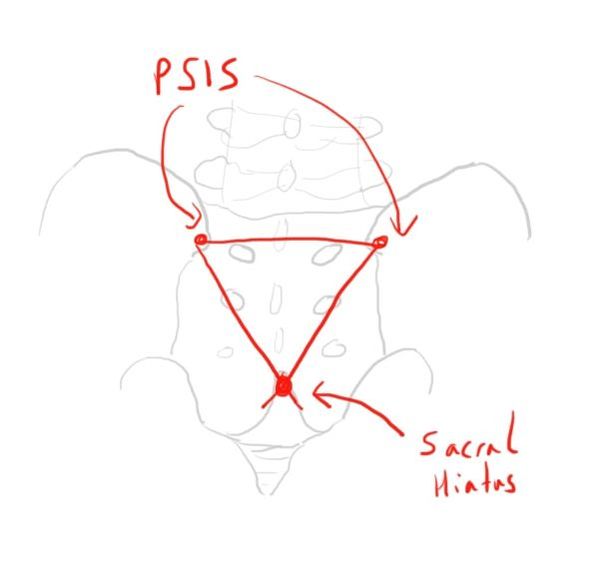

Identification of the posterior superior iliac spines (PSIS) is a starting point.

The line between these forms the base of an equilateral triangle, with the sacral hiatus being found at the third vertex.

This gives an estimation of where the site can be found, and it should hopefully be palpable.

The site can then be marked.

Identification of the posterior superior iliac spines (PSIS) is a starting point.

The line between these forms the base of an equilateral triangle, with the sacral hiatus being found at the third vertex.

This gives an estimation of where the site can be found, and it should hopefully be palpable.

The site can then be marked.

After careful cleaning of the skin (as for a neuraxial technique) and draping of the surrounding area, the technique can begin.

The skin is first infiltrated with some local anaesthetic e.g. 1% lidocaine.

The block needle is then inserted at this point, at an angle of about 45 degrees to the skin, aiming towards the head.

The needle is slowly advanced until a ‘pop’ is felt, as it passes through the sacrococcygeal ligament.

Now the cannula tube can be advanced over the needle into the epidural space by a few cm.

The cannula should be aspirated to confirm no CSF or blood.

In children a test dose is not usually possible (as they are usually anaesthetised) but should be performed in adults as with an epidural.

The block solution can then be injected.

In children the block dose will be:

Levobupivacaine:

0-6 months - 1-2mg/kg

>6 months - 2-2.5mg/kg

A maximum volume is 20ml.

A concentration of 0.25% is commonly used.

Addition of adjuncts can be used to prolong the effect of the block:

The skin is first infiltrated with some local anaesthetic e.g. 1% lidocaine.

The block needle is then inserted at this point, at an angle of about 45 degrees to the skin, aiming towards the head.

The needle is slowly advanced until a ‘pop’ is felt, as it passes through the sacrococcygeal ligament.

Now the cannula tube can be advanced over the needle into the epidural space by a few cm.

The cannula should be aspirated to confirm no CSF or blood.

In children a test dose is not usually possible (as they are usually anaesthetised) but should be performed in adults as with an epidural.

The block solution can then be injected.

In children the block dose will be:

Levobupivacaine:

0-6 months - 1-2mg/kg

>6 months - 2-2.5mg/kg

A maximum volume is 20ml.

A concentration of 0.25% is commonly used.

Addition of adjuncts can be used to prolong the effect of the block:

- Ketamine 0.5mg/kg

- Clonidine 1mcg/kg

This is a good example of the technique.

Credit to WFSA via Youtube. Link https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nWNUNQaZ3sI

Credit to WFSA via Youtube. Link https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nWNUNQaZ3sI

Complications

Caudal anaesthesia is generally very safe.

Recognised complications and adverse features include:

Recognised complications and adverse features include:

- Leg weakness (4-8%)

- Urinary retention (4-8%)

- Failure (2-10%)

- IV injection and toxicity (1 in 10,000)

- Infection/bleeding (1 in 80,000)

Links & References

- Candido, K. Winnie, A. Caudal anaesthesia. NYSORA. https://www.nysora.com/caudal-anesthesia

- Brown, D. Spinal, epidural and caudal anaesthesia, in: Millers Anaesthesia (7th ed).

- Patel, D. Epidural anaesthesia for children. CEACCP. 2006. 6(2): 63-66. Available at: https://academic.oup.com/bjaed/article/6/2/63/305090

- Allman, K. Wilson, I (eds). Oxford handbook of anaesthesia (3rd ed). 2012. Oxford University Press

- WFSA. Paediatric anaesthetics: Chapter 6 - Caudal (1). 2017. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nWNUNQaZ3sI