Anticoagulants

Last updated 18th October 2018 by Tom Heaton

There are a number of important drug classes used for anticoagulation.

Here we will look at:

- Warfarin

- Heparins

- DOACs

- Protamine

Physiology

To be able to understand how the different anticoagulants work, it requires some degree of understanding the normal physiological process of haemostasis.

There are some useful videos and resources on this topic here: http://www.medicalphysiology.co.uk/haemostasis.html

This video is also quite a good introduction to the topic, with some details on antiplatelet drugs too: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eZBtQ0rDnG4

There are some useful videos and resources on this topic here: http://www.medicalphysiology.co.uk/haemostasis.html

This video is also quite a good introduction to the topic, with some details on antiplatelet drugs too: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eZBtQ0rDnG4

Warfarin

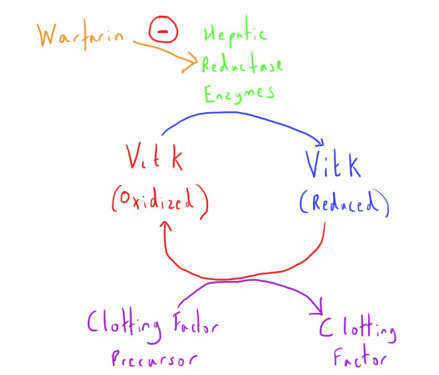

Warfarin is a coumarin derivative that has it's mechanism of action by disrupting the synthesis of vitamin K dependant clotting factors.

These clotting factors are II, VII, IX and X.

Vitamin K is also required for synthesis of the anticoagulant factors Protein C and Protein S.

Vitamin K is necessary for the gamma-carboxylation of glutamic acid residues of the clotting factor precursor proteins in the liver.

To provide this function Vit K needs to be in the reduced state.

Warfarin inhibits the hepatic reductase enzyme that causes this transformation.

Without this reduced Vit K, synthesis of these clotting factors is impaired.

The onset of warfarin’s action will be delayed until the pre-existing factors are depleted.

Factor VII has the shortest half life of the procoagulant clotting factors as so is the first to be depleted (hence why the INR measuring the extrinsic pathway is the most useful way of monitoring warfarin).

The other factors, especially prothrombin, will take longer to be depleted and hence the full anticoagulation effect is not noted until several days after initiation.

As noted, protein C and S are also vitamin K dependent, and these may be depleted first after onset of warfarin therapy.

As such, this may actually create a procoagulant state, and so warfarin must be commenced alongside other anticoagulant cover (e.g. LMWH).

These clotting factors are II, VII, IX and X.

Vitamin K is also required for synthesis of the anticoagulant factors Protein C and Protein S.

Vitamin K is necessary for the gamma-carboxylation of glutamic acid residues of the clotting factor precursor proteins in the liver.

To provide this function Vit K needs to be in the reduced state.

Warfarin inhibits the hepatic reductase enzyme that causes this transformation.

Without this reduced Vit K, synthesis of these clotting factors is impaired.

The onset of warfarin’s action will be delayed until the pre-existing factors are depleted.

Factor VII has the shortest half life of the procoagulant clotting factors as so is the first to be depleted (hence why the INR measuring the extrinsic pathway is the most useful way of monitoring warfarin).

The other factors, especially prothrombin, will take longer to be depleted and hence the full anticoagulation effect is not noted until several days after initiation.

As noted, protein C and S are also vitamin K dependent, and these may be depleted first after onset of warfarin therapy.

As such, this may actually create a procoagulant state, and so warfarin must be commenced alongside other anticoagulant cover (e.g. LMWH).

Pharmacokinetics

Warfarin is almost completely absorbed via the oral route.

It is very highly protein bound (>95%) which makes it vulnerable to being displaced, and therefore having increased activity, by certain drugs e.g. NSAIDs.

It is metabolised by the cytochrome P450 system of the liver with conjugated products that undergo biliary and some renal excretion.

The half life of warfarin is long at 24-36 hours.

It is important to note that the mechanism of action is not related to the pharmacokinetics of warfarin itself but is dependant on warfarin’s impact on the clotting factors.

Warfarin is almost completely absorbed via the oral route.

It is very highly protein bound (>95%) which makes it vulnerable to being displaced, and therefore having increased activity, by certain drugs e.g. NSAIDs.

It is metabolised by the cytochrome P450 system of the liver with conjugated products that undergo biliary and some renal excretion.

The half life of warfarin is long at 24-36 hours.

It is important to note that the mechanism of action is not related to the pharmacokinetics of warfarin itself but is dependant on warfarin’s impact on the clotting factors.

Indications

- Prophylaxis in AF

- Treatment of VTE

- Prophylaxis in metallic heart valves

Adverse Effects

- Haemorrhage - Anticoagulation is the obvious goal of warfarin therapy but this causes problems when there are drug interactions that affect its action or unforeseen event e.g. trauma, emergency surgery.

- Drug Interaction - One of the most common problems as warfarin's clinical effects can be impacted by a large number of drugs and substances that interact with plasma protein binding, P450 metabolism, Vitamin K uptake or that impact on other components of haemostasis. Common culprits include NSAIDs (compete for protein binding), some antibiotics (induce or compete for P450 system) and antiplatelets (increased incidence of bleeding).

- Teratogenicity - Crosses the placenta and can cause developmental problems (most commonly in the first trimester) or perinatal bleeding (if used in the third trimester).

Clinical Application

The large variety in individual responses to warfarin require its effects to be monitored.

This is done using INR measurements, with different targets for different clinical condition (a range of 2.0-3.0 is most common, with higher targets for conditions such as metal heart valves).

For similar reasons, careful initiation and titration is needed when starting warfarin to minimize the risk of bleeding complications and most organisations have their own regimes for achieving this.

Initiation much be especially careful in those with increased risk factors for supra-therapeutic levels e.g. chronic liver disease with pre-existing impairment of both clotting factors and plasma proteins for drug binding.

The large variety in individual responses to warfarin require its effects to be monitored.

This is done using INR measurements, with different targets for different clinical condition (a range of 2.0-3.0 is most common, with higher targets for conditions such as metal heart valves).

For similar reasons, careful initiation and titration is needed when starting warfarin to minimize the risk of bleeding complications and most organisations have their own regimes for achieving this.

Initiation much be especially careful in those with increased risk factors for supra-therapeutic levels e.g. chronic liver disease with pre-existing impairment of both clotting factors and plasma proteins for drug binding.

Overdose

Management of overdose of warfarin, as measured by an excessively high INR, will depend on the level of the elevation and whether there is any resulting bleeding.

A patient with an elevated INR who is actively bleeding will be treated very differently from a patient who is asymptomatic with the same INR value.

In general there are 3 options:

Management of overdose of warfarin, as measured by an excessively high INR, will depend on the level of the elevation and whether there is any resulting bleeding.

A patient with an elevated INR who is actively bleeding will be treated very differently from a patient who is asymptomatic with the same INR value.

In general there are 3 options:

- Simply withhold or reduce subsequent warfarin doses and allow a gradual return to the target range. This is the best approach in mild elevations without bleeding.

- Vitamin K1 (Phytomenadione) can be given when reversal is required but isn't needed immediately. A small oral dose (0.5 -2.5mg) will allow utilisation of the Vitamin K by the liver for subsequent clotting factor synthesis and so reversal of warfarin's effect. This is useful for patients with a more worrying INR (e.g. higher than 8.0) but without active bleeding.

- Rapid reversal may be needed when there is active bleeding occurring in the presence of an abnormal INR. Whilst higher dose intravenous Vitamin K allows more rapid synthesis of clotting factors, there is still some degree of delay whilst these are synthesised (perhaps up to 6 hours). If this is too long then clotting factors need to be administered to the patient. This can be in the form of fresh frozen plasma, or more specific clotting factor formula (recombinant factor VII, Prothrombin complex concentrate).

Heparin

Heparin is a naturally occurring component of the anticoagulant arm of the bodies haemostatic mechanism.

It is an anionic molecule of variable length that is synthesised in the liver and in mast cells.

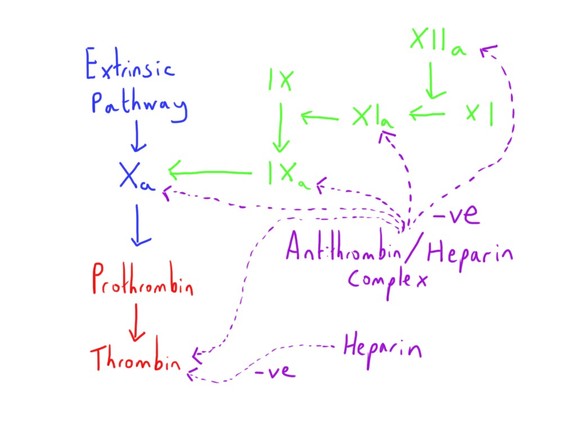

Antithrombin (a.k.a. Antithrombin III) is an anticoagulant factor that inhibits a number of the procoagulant factors: II (prothrombin), VIIa, IXa, Xa, XIa and XIIa.

This is normally only a fairly weak inhibition, but this action is potentiated around 1000 fold through combination with heparin.

This is particularly true of the inhibition of factors Xa and thrombin.

The result of this is that heparin strongly inhibits creation of new fibrin polymers and thus clot formation.

As such, it is used when a reduction in thrombus formation is needed for a clinical purpose.

This is particularly when the clinical need relates to the venous side of the circulation, as the coagulation cascade part of haemostasis has more of a role here (compared to the importance of platelets in the arterial side of the circulation).

Heparins are generally grouped into two distinct categories:

It is an anionic molecule of variable length that is synthesised in the liver and in mast cells.

Antithrombin (a.k.a. Antithrombin III) is an anticoagulant factor that inhibits a number of the procoagulant factors: II (prothrombin), VIIa, IXa, Xa, XIa and XIIa.

This is normally only a fairly weak inhibition, but this action is potentiated around 1000 fold through combination with heparin.

This is particularly true of the inhibition of factors Xa and thrombin.

The result of this is that heparin strongly inhibits creation of new fibrin polymers and thus clot formation.

As such, it is used when a reduction in thrombus formation is needed for a clinical purpose.

This is particularly when the clinical need relates to the venous side of the circulation, as the coagulation cascade part of haemostasis has more of a role here (compared to the importance of platelets in the arterial side of the circulation).

Heparins are generally grouped into two distinct categories:

- Unfractionated heparin (UFH)

- Low molecular weight heparin (LMWH)

UFH

LMWH

- Given by IV by infusion +/- initial bolus

- Rapid onset of anticoagulant action

- Can be titrated to effect

- Effect can be measured - APTT

- Less predictable effect (hence needs above monitoring and titration)

- Quickly reversible by protamine

LMWH

- Given subcutaneously

- More predictable anticoagulant effect (based on bodyweight) - monitoring not required in most cases

- Longer action - once daily regime

- Lower rate of heparin induced thrombocytopenia (HIT)

- Less predictably reversed

Pharmacokinetics

It is not absorbed orally.

It is negatively charged and with a low lipid solubility so does not membrane (e.g. BBB, placenta).

It is highly protein bound.

It undergoes hepatic metabolism by heparinases, with the products excreted renally.

A proportion is also excreted unchanged renally (up to 50%)

The elimination half life is short at 1-2 hours

It is not absorbed orally.

It is negatively charged and with a low lipid solubility so does not membrane (e.g. BBB, placenta).

It is highly protein bound.

It undergoes hepatic metabolism by heparinases, with the products excreted renally.

A proportion is also excreted unchanged renally (up to 50%)

The elimination half life is short at 1-2 hours

Indications

Via IV infusion a bolus and then infusion regime will commonly be used.

Titration it to a target aPTT time or ratio e.g. aPTT ratio of 2.0-3.0.

Activated clotting time (ACT) is another measurement that may be used in some clinical situations e.g. cardiac bypass.

- Treatment of VTE

- Prophylaxis of VTE

- Treatment of ACS

- Prevention of coagulation in extracorporeal circuits e.g. cardiopulmonary bypass, RRT.

- Prevention of thrombosis of metallic heart valves

Via IV infusion a bolus and then infusion regime will commonly be used.

Titration it to a target aPTT time or ratio e.g. aPTT ratio of 2.0-3.0.

Activated clotting time (ACT) is another measurement that may be used in some clinical situations e.g. cardiac bypass.

Adverse Effects

Heparin Induced Thrombocytopenia

There are two types of HIT.

Type 1 is an early (within 4 days) drop in platelet count due to heparin.

It is not immune mediated and rarely has any clinical significance.

Type 2 is a severe and serious complication.

It is discussed elsewhere.

- Bleeding

- Thrombocytopenia

- Hypotension following rapid IV administration

- Hypersensitivity reactions

- Osteoporosis

- Deranged liver function

Heparin Induced Thrombocytopenia

There are two types of HIT.

Type 1 is an early (within 4 days) drop in platelet count due to heparin.

It is not immune mediated and rarely has any clinical significance.

Type 2 is a severe and serious complication.

It is discussed elsewhere.

LMWH

This includes dalteparin, enoxaparin, tinzaparin.

The are smaller sized heparin molecules, with molecular weights more between 2000 and 8000 daltons.

They appear to have more activity inhibiting factor Xa.

It is usually administered SC, so onset will be delayed by 1-2 hours.

Excretion is mainly renal, and so affected by renal function.

Their half life is usually around 4-5 hours.

Monitoring of aPTT is less useful than with UFH (as much of the effect is from inhibition of factor Xa).

The are smaller sized heparin molecules, with molecular weights more between 2000 and 8000 daltons.

They appear to have more activity inhibiting factor Xa.

It is usually administered SC, so onset will be delayed by 1-2 hours.

Excretion is mainly renal, and so affected by renal function.

Their half life is usually around 4-5 hours.

Monitoring of aPTT is less useful than with UFH (as much of the effect is from inhibition of factor Xa).

Direct Oral Anticoagulants (DOACs)

These drugs were previously called NOACs (Novel oral anticoagulants) and have increased in clinical usage.

They refer to category of drugs that act in a different way from the historical methods of anticoagulants, targeting a more specific component of the clotting pathway, and being administered orally.

Although often grouped together, there a few few subgroups:

These drugs have the advantages of very predictable anticoagulant actions, so do not require monitoring.

Some other drugs have similar direct mechanisms of action, but aren’t administered orally.

There can generally be considered to be some advantages and disadvantages of the newer DOACs agent, which may be affecting anticoagulant practices.

Advantages:

Disadvantages:

They refer to category of drugs that act in a different way from the historical methods of anticoagulants, targeting a more specific component of the clotting pathway, and being administered orally.

Although often grouped together, there a few few subgroups:

- Direct thrombin inhibitors - dabigatran (has a T in the name)

- Direct factor Xa inhibitors - rivaroxaban, apixaban (have Xa in the name)

These drugs have the advantages of very predictable anticoagulant actions, so do not require monitoring.

Some other drugs have similar direct mechanisms of action, but aren’t administered orally.

- Direct thrombin inhibitors - argatroban, hirudin derivatives

There can generally be considered to be some advantages and disadvantages of the newer DOACs agent, which may be affecting anticoagulant practices.

Advantages:

- More predictable pharmacokinetics

- Less dose variation

- Monitoring not required - more convenient, potentially cheaper

- Less dose variation

- Fewer drug interactions

- Oral administration

- Rapid onset (no need for bridging)

- Potentially safer overall (under continuing study)

Disadvantages:

- No reversal agent (currently)

- Less clinical experience

- Rapid offset if dose missed

- Difficult to assess anticoagulation

Dabigatran

PD

This is a prodrug which is converted to an active form in the liver and plasma by esterases.

As noted, it is a direct thrombin inhibitor - this inhibition due to ionic binding at thrombin’s active site and is competitive and reversible.

It is inhibits both bound and free thrombin (unlike heparin)

PK

It has a BD dosing regime - 150mg BD, 110mg BD if over 80.

Oral absorption is good, with peak absorption at 1-3 hours.

Little further metabolism after initial conversation (some glucuronidation) - few interactions

Majority excreted unchanged renally - half life approx 12 hours.

Protein binding is low and it has a moderate volume of distribution.

Tests of coagulation are affected by Dabigatran in some ways (although evidence is scanty):

Indications

Cautions

This is a prodrug which is converted to an active form in the liver and plasma by esterases.

As noted, it is a direct thrombin inhibitor - this inhibition due to ionic binding at thrombin’s active site and is competitive and reversible.

It is inhibits both bound and free thrombin (unlike heparin)

PK

It has a BD dosing regime - 150mg BD, 110mg BD if over 80.

Oral absorption is good, with peak absorption at 1-3 hours.

Little further metabolism after initial conversation (some glucuronidation) - few interactions

Majority excreted unchanged renally - half life approx 12 hours.

Protein binding is low and it has a moderate volume of distribution.

Tests of coagulation are affected by Dabigatran in some ways (although evidence is scanty):

- INR - some elevation, but mainly at ‘overdose’ levels and not usefully

- aPTT - initial elevation at lower doses which tails off at higher doses

- Thrombin time - fairly linear rise. Perhaps most useful but standardisation can be a problem

Indications

- Stroke prophylaxis in non-valvular AF (with at least one additional stroke RF)

- VTE prophylaxis following elective THR or TKR

Cautions

- Renal dysfunction - half life notable prolonged when eGFR <30

Rivaroxaban

PD

This drug is a direct factor Xa inhibitor

PK.

It is administered orally with a good absorption.

It is highly protein bound (about 95%)

About ⅔ is metabolised hepatically, with the remainder excreted unchanged renally.

The half life is between 5 and 9 hours (although can be prolonged in the elderly.

It does not require monitoring.

It does have an impact on the PT or aPTT, but its effect is best measured using anti-factor Xa assay.

It is licensed for:

This drug is a direct factor Xa inhibitor

PK.

It is administered orally with a good absorption.

It is highly protein bound (about 95%)

About ⅔ is metabolised hepatically, with the remainder excreted unchanged renally.

The half life is between 5 and 9 hours (although can be prolonged in the elderly.

It does not require monitoring.

It does have an impact on the PT or aPTT, but its effect is best measured using anti-factor Xa assay.

It is licensed for:

- VTE

- Prophylaxis in AF

- VTE prophylaxis after hip and knee surgery

Apixaban

PD

This drug is a direct factor Xa inhibitor.

PK

It is administered orally.

It has a rapid onset time, peaking at 3 hours.

Half life is 8-13 hours.

Elimination is 75% faecal, with the remainder renal.

It does not require monitoring.

It does have an impact on the PT, but its effect is best measured using factor Xa assay.

It is licensed for:

This drug is a direct factor Xa inhibitor.

PK

It is administered orally.

It has a rapid onset time, peaking at 3 hours.

Half life is 8-13 hours.

Elimination is 75% faecal, with the remainder renal.

It does not require monitoring.

It does have an impact on the PT, but its effect is best measured using factor Xa assay.

It is licensed for:

- VTE prophylaxis after hip and knee surgery

Fondaparinux

PD

This is an indirect factor Xa inhibitor.

It is a synthetic pentasaccharide which is very similar to the active component of heparin which binds to antithrombin.

It has its effect by binding to antithrombin in a similar way to heparin, but enhances its effect at inhibiting factor Xa only.

PK

It is administered subcutaneously and has a predictable absorption and anticoagulant effect.

It has a relatively long half life (17 hours) which can be prolonged in the elderly.

It exhibits a low level of protein binding.

It may be possible to measure the anticoagulant activity using anti-Xa assays.

Indications:

Adverse effects

Bleeding is the primary adverse effect.

It has been used in patients with HIT, although this is still slightly controversial due to case reports of it being a trigger.

This is an indirect factor Xa inhibitor.

It is a synthetic pentasaccharide which is very similar to the active component of heparin which binds to antithrombin.

It has its effect by binding to antithrombin in a similar way to heparin, but enhances its effect at inhibiting factor Xa only.

PK

It is administered subcutaneously and has a predictable absorption and anticoagulant effect.

It has a relatively long half life (17 hours) which can be prolonged in the elderly.

It exhibits a low level of protein binding.

It may be possible to measure the anticoagulant activity using anti-Xa assays.

Indications:

- ACS

- Treatment of VTE

- Prophylaxis of VTE (post hip and knee surgery)

Adverse effects

Bleeding is the primary adverse effect.

It has been used in patients with HIT, although this is still slightly controversial due to case reports of it being a trigger.

Protamine

This is a reversal agent for heparin.

It is derived from salmon sperm (some people with fish allergy may be allergic)

It is positively charged molecule, binding with the anionic heparin molecules to produce an inactive complex - this occurs rapidly within 5 minutes.

This complex is then cleared by the reticuloendothelial system.

It is also found in some insulin preparation.

As well as its heparin binding, it exerts and mild anticoagulant and antiplatelet function in itself (hence an anticoagulant effect if too much given).

It is used at a dose of 1mg to reverse 100 units of heparin.

Adverse effects

It is derived from salmon sperm (some people with fish allergy may be allergic)

It is positively charged molecule, binding with the anionic heparin molecules to produce an inactive complex - this occurs rapidly within 5 minutes.

This complex is then cleared by the reticuloendothelial system.

It is also found in some insulin preparation.

As well as its heparin binding, it exerts and mild anticoagulant and antiplatelet function in itself (hence an anticoagulant effect if too much given).

It is used at a dose of 1mg to reverse 100 units of heparin.

Adverse effects

- Hypotension - can occur from histamine release so it is given slowly

- Allergic reactions

- Pulmonary hypertension

- Bradycardia

- Anticoagulant effect (if given in excess doses)

Links & References

- Heaton, T. Haemostasis. Medicalphysiology.co.uk. http://www.medicalphysiology.co.uk/haemostasis.html

- Koenig-Oberhuber, V. Flipiovic, M. New antiplatelet drugs and new anticoagulants. BJA. 2016. 117. https://academic.oup.com/bja/article/117/suppl_2/ii74/1744341

- O’Keeffe, N. Anticoagulants. e-LFH. 2018

- Peck, T. Hill, S. Williams, M. Pharmacology for anaesthesia and intensive care (3rd ed). 2008. Cambridge University Press.

- Nickson, C. Dabigatran and bleeding. LITFL. 2017. https://lifeinthefastlane.com/ccc/dabigatran-and-bleeding/

- Evers, A. Maze, M. Kharasch, E. (eds). Anaesthetic pharmacology: Basic principles and clinical practice (2nd ed). 2011. Cambridge University Press.

- Nickson, C. Rivaroxaban and bleeding. LITFL. 2014. https://lifeinthefastlane.com/ccc/rivaroxiban-bleeding/

- Nickson, C. New oral anticoagulants (NOACs). LITFL. 2015. https://lifeinthefastlane.com/ccc/new-oral-anticoagulants-noacs/