Acute Kidney Injury

This section will look at the following components of AKI:

- Definition/Classification

- Aetiology

- Presentation

- Investigation

- Prevention/Management

- Renal Replacement therapy

Definition

Acute kidney injury (AKI) is defined as a sudden decline in renal filtration function - it was previously called acute renal failure.

This functional decline can be demonstrated by:

Even more importantly, not all states of AKI result in oligouria - about 50-60% will not.

Indeed these are relatively poor markers of renal function, with waste markers not rising until over 50% of GFR is lost.

There are many more specialised tests of renal function, but they are of little use to front-line clinical staff.

Given this variation in presentation, particularly because of the widely varying pathophysiology, a clear set of criteria for diagnosis are need. The 2 most relevant criteria are the RIFLE and AKIN, with the KDIGO review also being an important document (though they endorse the the AKIN criteria).

A quick run through of these is helpful for understanding, but I think the KDIGO definition is the most up to date and useful.

This functional decline can be demonstrated by:

- An increase in the biochemical markers of renal function - creatinine and blood urea nitrogen (BUN).

- A decline in urine output - oligouria.

Even more importantly, not all states of AKI result in oligouria - about 50-60% will not.

Indeed these are relatively poor markers of renal function, with waste markers not rising until over 50% of GFR is lost.

There are many more specialised tests of renal function, but they are of little use to front-line clinical staff.

Given this variation in presentation, particularly because of the widely varying pathophysiology, a clear set of criteria for diagnosis are need. The 2 most relevant criteria are the RIFLE and AKIN, with the KDIGO review also being an important document (though they endorse the the AKIN criteria).

A quick run through of these is helpful for understanding, but I think the KDIGO definition is the most up to date and useful.

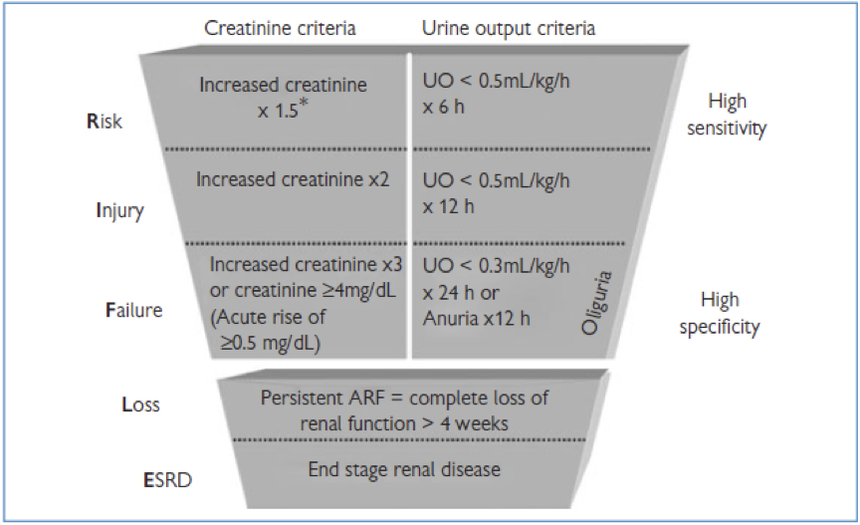

RIFLE Classification

The acronym RIFLE was developed in 2004 by the Acute Dialysis Quality Initiative (ADQI) and describes the successive stages of AKI - Risk of dysfunction, Injury, Failure, Loss of function, End stage kidney disease.

This is useful as it provides an progression of severity, with steps further along the criteria associated with worse outcomes e.g. mortality, degrees of return of kidney function.

The stages of the classification progress from highly sensitive to highly specific.

This is useful as it provides an progression of severity, with steps further along the criteria associated with worse outcomes e.g. mortality, degrees of return of kidney function.

The stages of the classification progress from highly sensitive to highly specific.

Image from lifeinthefastlane.com

As can be seen, the diagnosis can be made from either a creatinine level or urine output criteria, tackling the challenges noted above - the criteria that support the most severe level should be used

As can be seen, the diagnosis can be made from either a creatinine level or urine output criteria, tackling the challenges noted above - the criteria that support the most severe level should be used

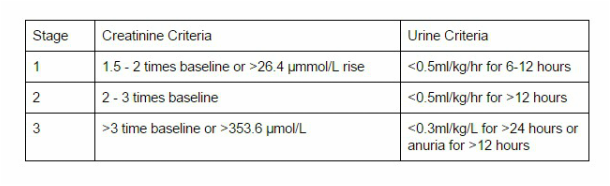

AKIN

The Acute Kidney Injury Network developed these criteria to help the diagnosis of AKI.

They simplified the classification into 3 stages, and lowered the threshold for inclusion as an AKI.

Again, a creatinine or urine output criteria could be used to reach the diagnosis criteria.

Of note, any requirement for renal replacement therapy counts as a level 3 AKI.

They simplified the classification into 3 stages, and lowered the threshold for inclusion as an AKI.

Again, a creatinine or urine output criteria could be used to reach the diagnosis criteria.

Of note, any requirement for renal replacement therapy counts as a level 3 AKI.

AKIN criteria for AKI

KDIGO

There are a few problems with each of these systems but both can be used.

The KDIGO group (Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes) published a large international guidance on the topic of AKI in 2012, reviewing all the evidence.

They recommend the AKIN classification system for grading of severity.

Their definition recommendations are (from reference 3):

The KDIGO group (Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes) published a large international guidance on the topic of AKI in 2012, reviewing all the evidence.

They recommend the AKIN classification system for grading of severity.

Their definition recommendations are (from reference 3):

- AKI is defined as any of the following:

- Increase in creatinine by 26.5 μmol/L within 48 hours, or

- Increase in creatinine over 1.5 times baseline, which is known/presumed to have occurred over the previous 7 days

- Urine output <0.5ml/kg/hr for over 6 hours

- AKI should be staged for severity, as per the AKIN criteria above.

- The cause of AKI should be determined wherever possible.

Aetiology

The causes of AKI are vast and varied.

The most common approach to classification is:

The most common approach to classification is:

- Prerenal

- Renal (intrinsic)

- Post renal.

1. Pre-renal

This is generally recognised as the most common cause of AKI.

The general mechanism is reduced blood flow the kidneys, and the cause of this can be further subdivided into different causes (think of the cause of shock to help):

2. Renal

This generally involves structural injury to the kidney - Acute tubular necrosis is the most common form that this takes, generally considered to be a result of prolonged pre-renal injury.

3. Post-renal

Any mechanical obstruction of the collecting system.

This is generally recognised as the most common cause of AKI.

The general mechanism is reduced blood flow the kidneys, and the cause of this can be further subdivided into different causes (think of the cause of shock to help):

- Reduced blood volume - haemorrhage, burns, dehydration

- Reduced cardiac output - MI, PE

- Vasodilation - sepsis, anaesthesia, anaphylaxis

- Impaired renal artery flow - abdominal compartment syndrome, artery stenosis, aortic cross clamping.

- Excessive afferent arteriole constriction - hypercalcaemia, hepatorenal syndrome, drugs (NSAIDs, Norad, Contrast).

2. Renal

This generally involves structural injury to the kidney - Acute tubular necrosis is the most common form that this takes, generally considered to be a result of prolonged pre-renal injury.

- Vascular - thromboembolic (arterial and venous), malignant hypertension, microangiopathy (e.g. DIC, pre-eclampsia).

- Tubular - cytotoxic - Haem (rhabdomyolysis), Crystals (tumour lysis, ethylene glycol), Drugs (amphotericin B, lithium, aminoglycosides

- Interstitial - Drugs (Penicillins, NSAIDs, PPIs), Infection (Pyelonephritis), Systemic disease (Lupus, Lymphoma, sarcoid)

3. Post-renal

Any mechanical obstruction of the collecting system.

- Ureteric stones

- Tumours - bladder, prostatic

- Strictures

- Prostatic hypertrophy

Presentation

As can be imagined from the very wide range of cause, there are many different features that can be discovered in the history.

This history should look at both the risk factors for development (e.g. PMH), and look at features that might suggest a exposure or specific pathology.

The list is large, but below are some examples.

Pre-renal - Features of dehydration, bleeding, fluid losses, critical illness

Renal - Nephrotoxic drug use, contrast exposure, pigment release (rhabdo, seizures)

Post-renal - sudden onset anuria, urinary tract symptoms.

Similarly the physical exam should assess for causes of AKI.

The list is again vast and requires a thorough systemic approach looking for the specific clinical signs of certain pathologies e.g. uveitis may be linked to a vascultic cause.

Given the very broad range of causes, yet the fact that most of the cases are caused by only a few common pathologies, the KDIGO group recommend a simple stepwise approach to evaluating AKI once it has been diagnosed

The flowchart of this can be found in the paper (open access).

This history should look at both the risk factors for development (e.g. PMH), and look at features that might suggest a exposure or specific pathology.

The list is large, but below are some examples.

Pre-renal - Features of dehydration, bleeding, fluid losses, critical illness

Renal - Nephrotoxic drug use, contrast exposure, pigment release (rhabdo, seizures)

Post-renal - sudden onset anuria, urinary tract symptoms.

Similarly the physical exam should assess for causes of AKI.

The list is again vast and requires a thorough systemic approach looking for the specific clinical signs of certain pathologies e.g. uveitis may be linked to a vascultic cause.

Given the very broad range of causes, yet the fact that most of the cases are caused by only a few common pathologies, the KDIGO group recommend a simple stepwise approach to evaluating AKI once it has been diagnosed

- Is there impaired perfusion? - look for evidence of this first from the history and examination findings - think fluid depletion, heart failure

- Is there obstruction? - again assess the history and examine specifically for this - id suspicion, perform ultrasound.

- Is there a specific diagnosis present? - think about the pathologies with a more specific history and feature e.g. glomerulonephritis, rhabo

- Try and categorise as a non-specific cause:

- Ischaemic

- Toxic

- Inflammatory

- Other

The flowchart of this can be found in the paper (open access).

Investigation

The investigations will involve some fairly simple initial tests, with a much broader range of specialist tests if a more exotic cause is responsible (I won’t cover these here)..

Initial tests will involve:

4. Renal tract US

Initial tests will involve:

- Serum biochemistry

- Full blood count

- Urinalysis with microscopy +/- urine biochemistry

4. Renal tract US

Prevention & Management

Much of the management of AKI is preventative and supportive with no specific treatments for the condition as a whole, only for specific pathology involved in it genesis e.g. obstruction.

The key general points of management of patients at high risk of AKI, and those who subsequently develop it include:

At the time that stage 2 AKI is reached then a step up in management is generally needed:

Again it is vital to emphasise that the prevention aspect is particularly important, especially given the degree of loss of GFR often needed to reach the criteria for AKI.

Alongside these general points there are a few key areas warranting specific discussion.

The key general points of management of patients at high risk of AKI, and those who subsequently develop it include:

- Avoid all nephrotoxic agents where possible - including radiocontrast

- Ensure volume status and perfusion pressure - consider functional CVS monitoring

- Avoid hyperglycaemia (target 6.1 - 8.3 mmol/L)

- Monitor serum creatinine and urine output.

At the time that stage 2 AKI is reached then a step up in management is generally needed:

- Consider the initiation of renal replacement therapy at this time

- Review drug dosing in these patients.

Again it is vital to emphasise that the prevention aspect is particularly important, especially given the degree of loss of GFR often needed to reach the criteria for AKI.

Alongside these general points there are a few key areas warranting specific discussion.

Fluids

Fluid therapy is often seen as the mainstay of treatment because fluid depletion is such a risk factor for AKI.

Maintaining an appropriate ‘volume status’ is therefore important, but it is important to also bear in mind the increased mortality with fluid overload state.

The evidence about the type of fluids isn’t great but perhaps leans towards:

In general avoid both under and overhydration by clinical assessment of their status and use of vaso-active drugs when indicated.

Maintaining an appropriate ‘volume status’ is therefore important, but it is important to also bear in mind the increased mortality with fluid overload state.

The evidence about the type of fluids isn’t great but perhaps leans towards:

- A balanced crystalloid is probably the best general fluid

- Normal saline can be used but may result in more biochemical disturbance due to it’s ‘abnormal’ electrolyte balance.

- Colloids don’t have any evidence of benefit so have no real specific place unless other clinical indications.

- The hydroxyethylstarch (HES) colloids are probably nephrotoxic though so should be avoided.

In general avoid both under and overhydration by clinical assessment of their status and use of vaso-active drugs when indicated.

Vasopressors

Again the evidence for vasopressor choice once volume status has been optimised isn’t fully clear. Some points:

- The use of vasopressors shouldn’t be withheld for fear of detrimental renal effects, and indeed it can be beneficial to maintain the perfusion pressure.

- Vasopressin may have some renal benefits but the evidence for this is not compelling

- Noradrenaline therefore still probably remains the standard first choice.

Diuretics

On balance of the evidence:

- Furosemide is either no use or harmful in AKI - its use isn’t recommended.

- It can be used as part of a fluid balance strategy though.

- There is pretty much no evidence for the use of mannitol.

Vasodilators

- The use of dopamine for its vasodilator properties has been explored and shown to be of no benefit but with a number of adverse effects - it should be avoided/

- The evidence for fenoldopam (a pure dopamine type-1 receptor agonist) is also sparse, with the risk vs benefit currently not justifying its use.

Nutrition

- The vogue for intensive insulin therapy has been shown to probably be associated with more risks (severe hypoglycaemia) than benefits (minimal).

- However hyperglycaemia should be avoided - a target range suggested by the KDIGO group is 6.1 - 8.3 mmol/l

- It should be noted that a number of water soluble nutrients are lost through continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT).

- There is also the increased metabolic demands of critical illness to bear in mind

- Specific nutritional recommendations (from KDIGO) include:

- Target energy intake of 20 - 30 kcal/kg/day

- Protein intake of 0.8 - 1.0 g/kg/day if not on RRT

- Increased to 1.0-1.5 g/kg/day if on RRT

- Increased up to max 1.7 g/kg/day if hypercatabolic and on CRRT.

Contrast Induced AKI

This is a well known and specific cause of AKI that warrants further discussion.

It is the impairment in renal function following administration of IV contrast for certain radiographic procedures.

The KDIGO group recommend using the same thresholds, in terms of creatinine rise and urine output, for defining the condition.

It exhibits its toxic effect through a number of mechanisms:

There are a number of risk factors for the development of CI AKI, which can be split into patient factors, and procedure factors.

Patient factors:

The KDIGO group identify that a threshold of risk is probably an eGFR of 45 ml/min per 1.73 m^3.

However, they discussed that some risk, justifying preventative measures, may be warranted below an eGFR of 60ml/min per 1.73 m^3.

The most important step in prevention is careful consideration of the risk of CI AKI in patients for whom imaging is planned, and a consideration of alternative strategies to minimise the risk (including alternative, non-contrast imaging).

Volume expansion is the most important next step in prevention.

There is suggestion that using sodium bicarbonate as the expansion fluid may have some beneficial effects, but there is some potential for harm from this approach, so simple normal saline is commonplace.

The only other treatment recommended for prevention of CI AKI is oral N-acetylcysteine in patients with increased risk - there is some suggestion of benefit (though not overwhelming) but the oral route minimises some of the adverse effects from the IV route.

It is the impairment in renal function following administration of IV contrast for certain radiographic procedures.

The KDIGO group recommend using the same thresholds, in terms of creatinine rise and urine output, for defining the condition.

It exhibits its toxic effect through a number of mechanisms:

- Direct cytotoxic effect

- Increased vasoconstriction, particularly of the already vulnerable medulla

- Increased blood viscosity, with impaired flow

- Increased activation of reactive oxygen species

There are a number of risk factors for the development of CI AKI, which can be split into patient factors, and procedure factors.

Patient factors:

- Baseline renal function

- Age

- Effective volume status e.g. hypovolaemia

- Diabetes mellitus

- Hypertension

- Volume of contrast

- Type of contrast (osmolality, viscosity)

- Arterial vs venous

- Urgent

The KDIGO group identify that a threshold of risk is probably an eGFR of 45 ml/min per 1.73 m^3.

However, they discussed that some risk, justifying preventative measures, may be warranted below an eGFR of 60ml/min per 1.73 m^3.

The most important step in prevention is careful consideration of the risk of CI AKI in patients for whom imaging is planned, and a consideration of alternative strategies to minimise the risk (including alternative, non-contrast imaging).

Volume expansion is the most important next step in prevention.

There is suggestion that using sodium bicarbonate as the expansion fluid may have some beneficial effects, but there is some potential for harm from this approach, so simple normal saline is commonplace.

The only other treatment recommended for prevention of CI AKI is oral N-acetylcysteine in patients with increased risk - there is some suggestion of benefit (though not overwhelming) but the oral route minimises some of the adverse effects from the IV route.

Renal Replacement Therapy

This is a massive topic and I shall put together an independent set of notes on it.

Of note here, the five classic indications for RRT are when the following conditions are severe and not responsive to maximal medical therapy:

Of note here, the five classic indications for RRT are when the following conditions are severe and not responsive to maximal medical therapy:

- Hyperkalaemia

- Acid/base disturbance

- Pulmonary oedema/fluid overload

- Uraemia

- Removal of toxins

A good mnemonic is to use all the vowels - A, E, I, O, U:

A: Acid/base

E: Electrolytes

I: Intoxication

O: Oedema/Overload

U: Uraemia

A: Acid/base

E: Electrolytes

I: Intoxication

O: Oedema/Overload

U: Uraemia

References

- Medscape - Acute Kidney Injury. Accessed 13/1/2016. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/243492-overview

- Life in the fast lane - RIFLE and AKIN criteria. Accessed 13/1/2016. http://lifeinthefastlane.com/ccc/rifle-criteria-and-akin-classification/

- Kellum et al. Diagnosis, evaluation and management of acute kidney injury: a KDIGO summary (Part 1). Critical Care. 2013. 17:204. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4057151/

- Lameire et al. Contrast-induced acute kidney injury and renal support for acute kidney injury: a KDIGO summary (Part 2). Critical Care. 2013. 17:205 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23394215

- Bersten A, Soni N. Oh's Intensive Care Manual (7th ed). 2014. Butterworth Heinemann Elsevier.